How useful, overhyped, or even detrimental are digital technologies in a crisis? Zoom came in to save the day when work went remote during the COVID-19 pandemic, online shopping and food delivery grew rapidly, even doctors’ appointments went online. What can be learned from experiences of crisis-driven technology use, both on an individual and organizational scale?

Subscribe:

For many, these digital technologies and even more specialized innovations provided a kind of utopian hope for large-scale societal change. In reality, the acceleration of digital innovation across sectors and the world has disrupted business as usual and exposed systemic challenges and inequalities. This is what Cambridge professor Michael Barrett points out on the Delve podcast as he discusses his latest research examining the possibilities and limits of digital innovation.

In December of 2022, Professor Barrett gave the Laurent Picard Distinguished Lecture at Desautels on the subject of rethinking digital innovation and crisis. He outlined his recent research that examines digital innovation in organizations and asks what happens with that innovation in a time of crisis, including at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Barrett’s research is immersed in digital innovation research, organizational strategy, and institutional change—it has looked at the uses of AI, 3DP, telemedicine in hospitals, mobile payment services, clean energy, technologies for climate resilience, and more technologies and their impacts.

Delve: Some organizations introduce new technologies before they’re perhaps equipped to do so, such as in a time of crisis. However, in an ideal situation, can organizations be fully prepared to introduce new technologies? Or should they always plan for some degree of the unexpected?

Michael Barrett: One is never fully prepared for any eventuality, such as a crisis. But there is what a level of digital maturity of the organization, which may depend on the resources that they have, but not just the resources: the mindset change that they have as to the possibilities and the potentialities of the new technology, and the actual practical ways of understanding and testing the limits and possibilities of the digital innovation. Depending on the amount of work or that digital maturity, the resources, the capabilities, the readiness for change, and the infrastructure to deliver the technology, an organization will be less or more prepared, regardless of the eventuality.

Delve: Could you define what a crisis is, in relation to your most recent research, where you write that a crisis can be an opportunity for the organization, but not in all organizations or not all crises.

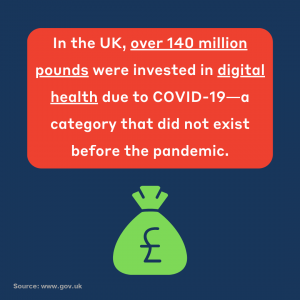

Michael Barrett: There are different types of crises and there are different conditions of crisis. The different images of crisis we’ve looked at in our research categorize them into crisis as opportunity versus crisis as disruption or crisis as exposure. They are all images and vantage points, but they’re helpful to make sense of the crisis and to understand the different ways in which digital technologies might respond to those crises. The opportunities that we see through COVID are huge investments—in the UK over 140 million pounds in a short period of time into digital health, a sector that had relatively little investment as a category up to that point in time.

Any crisis will disrupt work practices in ways that challenge routines that have a need for new ways of operating.

Any crisis will disrupt work practices in ways that challenge routines that have a need for new ways of operating. We have seen how at scale, digital platforms allow us to engage in activities, whether it’s telemedicine, whether it’s learning opportunities or sales meetings through Zoom, many things that we knew were possible, but didn’t scale anywhere near that. But we must also always look at the tension and the critical issues that might produce new risks, in that these platforms are becoming increasingly indispensable and overdependence on them raises concerns.

Crisis also sheds a spotlight on those that are vulnerable. It’s really important to realize that crisis exposes the invisible work becoming visible, those that are in situations of low socio-economic conditions, for instance. We did see in many studies on the COVID-19 pandemic, that there are increasing digital inequalities that have exacerbated the digital divide. And that is something which we argue is important as a moral imperative to us all to address.

Delve: There’s a persistent utopian vision that digital innovation can solve the world’s problems, but obviously so many of those problems—like poverty, homelessness, lack of access to health care—haven’t gone away despite the world’s technological leaps. These socio-economic inequalities came into sharp relief during the COVID crisis. With that in mind, could you share how the organizations that you researched, especially hospitals, used technological innovation to help them manage in crisis. You have the example of the ophthalmology unit of a major London hospital, which introduced telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic to serve its patients, which included many older vulnerable patients. The hospital went from the tried-and-true slit lamp method of diagnosing eye problems in person to determining risk of eye problems through telemedicine, through video chat essentially. But even before the pandemic, you were drawn to look deeper at this hospital and how it functions—why was that?

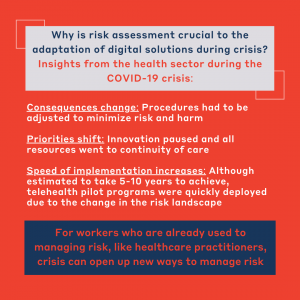

Michael Barrett: We were drawn to it because we always look for where there is opportunity for learning at extremes. [At the hospital] the focus had to be on how they kept care going and how telemedicine allowed for ophthalmology to be continued… They scaled up within three months to 10,000 video consultations, which was just mind blowing to them and for us as well. What we learned through that was it’s not that the telemedicine had changed—it remained the same technology—but the risk landscape within which the introduction of the technology was being introduced was changing in a way that led to a lot more openness for certain conditions for the clinicians to provide the care. And in doing so to adjust their procedures and approaches to delivering the care that was sensitive, to keep the risks and the potential harm minimized as to how they saw it before the crisis. It was a surprise to all, including the clinicians, many of whom I had no expectation or intention of delivering care through the telemedicine—because why would you if you feel that your profession largely involves a physical examination around a slit lamp with the person beside you, that that is the best way of making a judgment and a diagnosis. Why would you change?

Delve: A health care center or hospital is a place where risk is tangible, more tangible to the general population than in other areas since it’s something we all relate to, our health, our quality of life and the risks to it, such as harm and death. How did your research define risk in relation to new digital technologies and understanding and weighing risk? And why is it important, especially to decision makers at an organization such as a hospital to understand that risk is socially constructed? You did both quantitative research and qualitative research to show that risk is more of an ecology, a series of relationships, rather than a more easily quantifiable measure.

It’s that balance of understanding the nature of the industry, the risks of the risk landscape, and the changing risk landscape.

Michael Barrett: In a tightly regulated context, like healthcare, it is important to protect the patient, and the professional socialization of a doctor, doing no harm, is a very strong impetus for not taking risks that are seen to be risks. Our usual way of thinking of digital innovation may center on showing the value. And indeed, that is very important: you show the value also by implementing it effectively. But the challenge becomes about its value for whom. This whole sense of the risk that you’re willing to take becomes a risk related to the uncertainty that it provides, especially and only if it’s of value to a particular “object at risk,” or humans in this case. It’s that balance of understanding the nature of the industry, the risks of the risk landscape, and the changing risk landscape. We see that very clearly in a crisis of a COVID-19 risk, which was impacting the user journey of elderly people who might be vulnerable; therefore it was life threatening to come in [to hospital] to do a physical examination, even if that is the preferred and the best way clinically, the patient was now at risk and at harm. So it left an opening in that risk ecology for telemedicine, for the same technology to be seen it as less risky and doing less harm for the patient than if you ask them to come in to the site for a physical examination.

Delve: The pandemic also shone a spotlight on the broader health care crisis in general, which has endured and expanded, but also become more of a focus for governments, policy makers and citizens as well. In your research and theories of risk and technologies, there’s the sense of learning more about solutions to long-term crisis. Could these parts of your research be applied to different areas outside of health care?

Michael Barrett: I really do believe they can. But like all research, which is more qualitatively oriented, we have to be specific as to the boundary conditions and the kinds of things that may be generalizable, what we often refer to as analytical generalizability, as opposed to statistical generalizability, which you would try to do in a quantitative study. But I do believe the principles, the ideas, the insights that we’re learning around the changing risk-scape and risk ecology, how we consider and designate those as a social construction of what risk objects are and how they get translated, are very helpful regardless of the industry. I think it tells us more about generally how we organize for risk, especially with digital innovation. But context is king, in the sense of how we think through the principles and the ideas: what are the insights and the learnings that we can get across multiple sectors? I would definitely encourage not being restricted to a single sector but to appropriate the ideas and the concepts in ways that are so sensitive to the context but still willing to be bold and experiment and see the opportunities for insights from this work more widely.

For further insights and information, listen to the full interview with Michael Barrett on the Delve podcast.

This episode of the Delve podcast is produced by Delve and Robyn Fadden. Original music by Saku Mantere.

Delve is the official thought leadership platform of McGill University’s Desautels Faculty of Management. Subscribe to the Delve podcast on all major podcast platforms, including Apple podcasts and Spotify, and follow Delve on LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube.