Why is being overqualified for a sought-after job at a desirable workplace seen as a drawback? When job hunting, people give all kinds of obvious and not-so-obvious signals about their capabilities and their “fit” for an organization. In resumes and in job interviews, they’ll highlight work experience, education, skills, and in general try to prove their worth in that particular corner of the labour market. What happens when even the most qualified job applicants do everything right but end up seeming overqualified anyway?

Subscribe:

Despite having prestigious educations and impressive work credentials, these candidates get turned down by hiring managers, often before they even get an interview. Are they to blame for striving too much? Or are prospective employers biased against over-achievers? Turns out, it’s a bit more complicated than that.

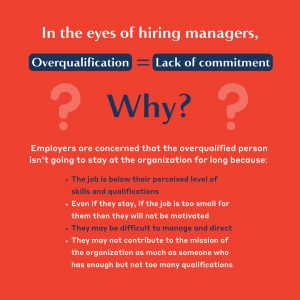

Desautels Faculty of Management Professor Roman Galperin and his co-researchers ran experimental studies to figure out what hiring managers really thought about these exceptionally qualified job candidates. They found that the signals that candidates give about their capability for a job are linked to hiring managers’ perceptions of commitment—namely, the concern that overqualified applicants are a flight risk.

On the Delve podcast, Galperin discusses why that is, what people can do about it when navigating the labour market, and why prospective employers should think again about these overqualified, highly knowledgeable job seekers—especially in a time when AI technologies are increasingly applied in the workplace.

The labour market has clearly changed over the past few years since the COVID pandemic began, and continues to face changes to how people look for jobs, how they do their jobs, and how often and why they change jobs. Stemming from his and his co-researchers’ experiences out of graduate school at MIT, and encompassing numerous conversations with other overqualified job hunters as well as hiring managers, Galperin’s research paper shows that overqualification means different things to different employers. At the same time, some job applicants don’t feel they’re overqualified, even if a potential employer perceives them that way during an interview or on their resume.

“You invest in something that increases your skills, and then it’s really hard to find a job,” Galperin explains. “We started thinking about this and developed this into the idea that overqualification is something that most of us have heard about but we really don’t quite know how it works and what it is.”

Qualifications, commitment, and perception

The discoveries that emerged from the research fell within two themes. One, the concern that the overqualified person isn’t going to stay at the organization for long because the job is so below their perceived level of skills and qualifications. Two, that even if they stay, if the job is too small for them then they will not be motivated, may be difficult to manage and direct, and may not contribute to the mission of the organization as much as someone who has enough but not too many qualifications.

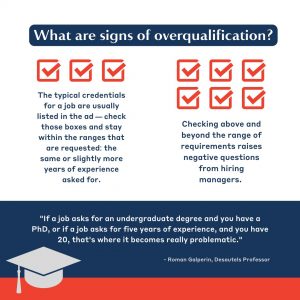

Galperin also points out that while education and experience levels might raise an eyebrow, job titles on resumes matter too. Even with the same level of education and qualifications, if someone has moved up the title ladder into management or the executive level, but are now applying to positions below that, then potential employees will likely wonder why they appear to be taking a step down in their career. These signals in the hiring process are questions marks or even doubts in the mind of the hiring manager.

This is a perennial problem.

“This is a perennial problem, and the reason that we haven’t talked about commitment as much among researchers of labour markets is not because it hasn’t been happening, it’s just we haven’t paid enough attention to it,” says Galperin. “This in part may be related to the fundamental feature of commitment—that it’s very difficult to measure. It’s hard to know how much someone is committed to something. It’s really easy to say that you’re committed, but it’s been difficult to check to what extent this is true. This is an important question because it affects how people actually hire others and help people find jobs.”

Finding the right fit for the right qualifications

What can people who are looking for a job and what can employers for that matter learn from this link between overqualification and commitment? Should prospective employees who are overqualified present themselves differently? Is there something more strategic that they should do? Or is this a larger contextual, systemic problem with the labour market in general?

“Maybe the simplest way to think about this is to question when considering getting another degree or considering getting a credential, a license or certification, is that more is not always better in this regard,” says Galperin. “And that if there is concordance between where you are in your career and what kind of qualifications you have, you’re in good shape. But if not, if you’re considering getting an MBA right after an undergraduate degree, this may not be a good idea—because when you’re applying for an entry level job, it’s more of a liability. You will need to explain why it is that you’re applying with an MBA to an entry level job.”

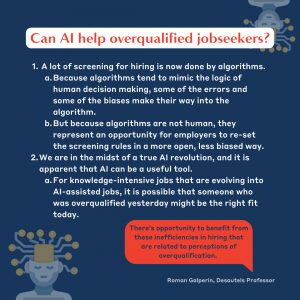

Yet applicants should still try to offer explanations for their overqualifications in a cover letter or in their resume—especially since a lot of screening today is done through automation.

“A lot of job screening is done by algorithms today,” explains Galperin. “Because algorithms tend to mimic the logic of human decision making, some of the errors and some of the biases may make their way into the algorithm. But they’re also different; they’re also not humans. So there is opportunity in that difference, in setting the rules for the algorithm in a more open, maybe a little bit stricter, less biased way. There’s opportunity to benefit from these inefficiencies in hiring that are related to overqualification or the perception of overqualification.”

AI can be a useful tool, especially in knowledge-intensive jobs.

While the conundrum of overqualification for a job has been around for many years, the advances in AI technology have complicated it even further. Yet with every new technology, especially those as groundbreaking as AI, comes new opportunities.

“We are in the midst of experiencing a true AI revolution, we’ve talked about this for several years now,” Galperin says. “But now, it is apparent that AI can be a useful tool, especially in knowledge-intensive jobs. If we imagine the evolution of knowledge-intensive jobs into those that are AI-assisted jobs, it’s possible that someone who seemed overqualified for the job yesterday, today will be just the right fit… People who seem overqualified now will not be overqualified tomorrow with the same level of qualifications.”

For further insights and information, listen to the full interview with Roman Galperin on the Delve podcast.

This episode of the Delve podcast is produced by Delve and Robyn Fadden. Original music by Saku Mantere.

Delve is the official thought leadership platform of McGill University’s Desautels Faculty of Management. Subscribe to the Delve podcast on all major podcast platforms, including Apple podcasts and Spotify, and follow Delve on LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube.