Banks and institutional investment funds are increasingly committed to net-zero carbon targets by 2050, joining numerous institutions, companies, and not-for-profit organizations in Canada and around the world in their sustainability goals. What does the road to net-zero look like in the realm of long-term investment, who are the players, and how should the inevitable roadblocks be overcome?

Delve’s video and accompanying article are excerpted from the Desautels Faculty of Management Integrated Management Symposium, The Road to Net-Zero, held on November 2, 2022, co-presented by Delve.

One of the biggest challenges today for financial institutions is how to meet climate targets while achieving high returns on investment and satisfying the needs of various stakeholders. The design of a net-zero pledge and decarbonization strategy, especially for large pension funds, has become a global challenge—this year also taken up by 96 student teams from 21 countries for the 2022 McGill International Portfolio Challenge (MIPC).

Reflecting that challenge and diving into how to achieve net-zero to ensure a sustainable future for current and subsequent generations, institutional investment experts Fanny Doucet, CFA, Managing Director & Head of Sustainable Finance at Scotiabank, and Lori Kerr, CEO of FinDev Canada, Canada’s development finance institution, shared their insights at Desautels Delve’s MIPC symposium with moderator Desautels Professor Sebastien Betermier.

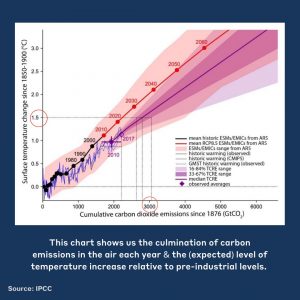

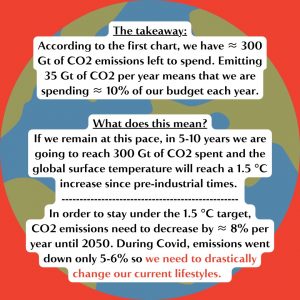

Today, the cumulative stock of global carbon emissions is directly linked with the global level of temperature increase, relative to preindustrial levels. Betermier points out that this remarkably linear relationship indicates that to maintain a 1.5-degree target for emissions, the world must stay within its remaining carbon budget of roughly 300 gigatons of CO2. At the current carbon use of 10% per year, the target will be met or exceeded in five to 10 years.

“We’re exhausting our budget,” says Betermier. “The carbon decrease during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic was about 6%. We need to reach 8% per year, every single year from now to 2050. This is serious.”

We need to reach 8% per year, every single year from now to 2050.

Reducing carbon dependence at a higher rate than it stands today requires global collaboration that bridges the public and private sectors, including large investment managers, and incorporates sustainability into governmental and corporate goals. As capital providers, public and private banks have a key role in leading the way in this transition.

Measuring progress and speeding up action

“Are we going fast enough to meet our net-zero target? I think that we’ve got a long way to go,” says Kerr. She adds that three components will determine that progress: the state of goal setting globally today (she gives it a 7 out 10); the information and data needed to achieve those goals and determine the pathways to decarbonization at the national level, corporate, and individual levels (five out of 10); and the incentives that impel action (three or four out of 10).

“What we do know is that we can have a huge impact on the goals that we’ve set,” Kerr says. “For incentives, we need both sticks and carrots to make action happen. We’ve got a long way to go to be able to keep 1.5 alive. But I’m an optimist; I have to be an optimist. One has to be an optimist when you’re in the climate and the sustainability field. I think we can turn those numbers around.”

In the past two years leading up to the COP 26 UN climate change conference, which brought together 120 world leaders and over 40,000 registered participants, the momentum has picked up significantly for setting goals around emission targets.

“About 85% of emissions right now are covered by countries that have set net-zero ambitions, and about a third of publicly traded companies have set net-zero emissions targets for 2050,” says Doucet. “It really does require a partnership between the private sector and the public sector. We do need more incentives to get this going quickly, and we need bold steps taken by governments and the public to incentivize the private sector as well.”

A third of publicly traded companies have set net-zero emissions targets for 2050.

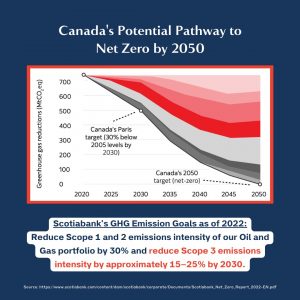

To meet net-zero targets, carbon intensity must decrease to zero alongside absolute carbon emissions. Currently in Canada, carbon intensity is decreasing, showing that Canada has become more energy efficient. However, absolute emissions continue to increase.

“The goal is to reduce real-world emissions; we can’t just reduce emissions intensity,” says Doucet. “The reason that we see a lot of emissions intensity reduction targets is because it provides a lot more information to be able to make decisions on—although the focus should be on reducing absolute emissions.”

Doucet also recommends having 1) data for both targets, and 2) setting a baseline year to measure progress against and measure a trendline. “Having data means having processes, and this is where a lot of the work comes in,” she explains. “If you’ve done work around that baseline, and work around where you think you can go, you can set targets for emissions reduction… You can’t manage what you can’t measure.”

Why banks have a unique role to play

Banks, whether public or private, play a critical part of the global financial ecosystem as capital providers to both traditional industries and new renewable energy green industries.

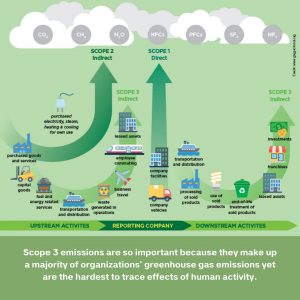

“It’s a unique role that banks play in this transition,” says Doucet. While many organizations, including banks, have committed to net-zero in their operations, the bulk of their emissions come from elsewhere, such as the product emissions they finance in the real economy. These are considered “scope 3” emissions.

“That puts us in a unique position in which there are great things we can do with our own operations, but we also work with our clients to help them through the transition as capital providers,” says Doucet. “We have to be advisors, we have to be influencers, and we really have to put ourselves out there to help our clients. It is different [than a corporate perspective that primarily looks at operations], but very exciting because we actually get to work with clients across our global footprint, across multiple different industries, and help them with their transition process.”

Part of being an influential player with capital is that we have to support our clients in making good decisions.

One of the main differences between public and private banks is the number of depositors, with public banks typically having one big client: governments.

“Even though we are a public bank, we are also a capital provider,” says Kerr about FinDev Canada, which functions as a development finance institution that supports private investments in emerging markets, providing both debt products and equity products. The institution brings a broader sustainability framework to the table and focuses on three impact goals in every investment it makes: gender equality in economic empowerment; market development; and climate action. As a relatively new institution at five years old, FinDev is net-negative and doesn’t finance oil and gas.

“Part of being an influential player with capital is that we have to support our clients in making good decisions,” says Kerr. “We’re just coming at it from different parts of the ecosystem.”

How to take collaborative action

In some cases, especially with new climate-related and complex green projects, a certain amount of public funding can help mitigate perceptions of risk and attract private capital.

“A key piece of the net-zero discussion is the concept of collaboration in terms of countries having to come together with net-zero goals, and companies coming together across the public and private sector,” says Doucet.

A key piece of the net-zero discussion is the concept of collaboration.

Significant scope 3 reductions require collaboration all along the supply chain. For example, blended finance can foster investment in sustainability projects that would otherwise pose a high risk and not enough return to private sector investors like banks, which operate within a required risk and return framework. Public organizations can reduce some of that risk by providing “a first last piece” so that if a project loses money, they cover that loss first or accept only a small return on their part of the capital, while the private capital accepts a higher return.

However, one of the challenges with blended finance is that it is often bespoke, requiring due diligence and commitment by all organizations. In that sense, however, each instance is difficult to replicate and to scale.

“Trying to figure out how to mobilize private capital at scale by using blended finance is something that we’re very much working on,” says Kerr, pointing out that blended finance can be used at the transaction level as well as the platform level. For example, FinDev Canada works with a Canadian pension fund and a global bank, structuring a blended finance platform that integrates concessional finance in a first loss position to address the risk-return appetite of the private sector. Those proceeds will be used for national infrastructure projects, “so it’s mobilizing capital at scale into infrastructure.”

Doucet has seen collaboration bridge different types of organizations across the supply chain. “They help each other one because they need to, because the world needs it, and because they need to reduce their scope 3 emissions,” she observes.

Kerr adds that governments at all levels also have an important responsibility to create an environment in which the private sector can invest in projects (as well as build, own, operate, and finance) and in which collaborations are fostered: “Governments have a huge responsibility to raise the bar and set those sustainability standards.” That can mean making decisions on renewable energy on a public grid, on public transportation, and beyond.

Essential investments for achieving net-zero

Looking at what can be done right now, what are the best ways to get to net-zero by 2050? Doucet suggests more investment in innovation and new technologies that will help with the energy transition—but “the problem is a lot of the technologies are as of yet unproven, so it can be risky.” She also suggests that more money flow to emerging markets: “They certainly need the support of economies like Canada, the U.S., and Europe to transition. We have to think about a just transition, and remember that emissions are global.”

Kerr echoes the call for more money in emerging markets, as well as improving energy transmission infrastructure. She adds that getting countries to transition away from coal is imperative, as is spending on research and development for decreasing carbon and increasing new sources of energy. Lastly, solutions to high land-use emissions must be found, such as regenerative agriculture.

Reaching net-zero requires a global effort that is as financial as it is cultural: a sea change stemming from decision-making with sustainability at its core.

For more insights, watch the Delve video of the symposium.

Fanny Doucet

Sustainable Finance, Scotiabank

Lori Kerr

FinDev Canada

Sebastien Betermier

Desautels Faculty of Management

Article written by: Robyn Fadden

This Delve video is excerpted from the Desautels Faculty of Management McGill International Portfolio Challenge 2022 symposium event, held on November 2, 2022 as part of the Marcel Desautels Institute for Integrated Management (MDIIM) and Delve Integrated Management Symposium Series.

Delve video editing by: Sofia Chaudruc, from original video by McGill Office of the Vice-Principal.

Photo by: Owen Egan