Two hallmarks of digital technology are that it evolves rapidly and touches virtually every aspect of our lives. Technological adoption in banking and the financial intermediation sector is no exception. Reliant on digital technologies, transaction settlements move funds from cardholder accounts to merchants’ accounts and are used for everything from credit cards to cryptocurrencies. Central Bank Digital Currencies represent a possible next step, with advances in privacy, fraud protection, and efficiency—but their roles and risks on the high-tech path forward are only now becoming clear.

Article written by: Ty Burke

Illustration by: Sébastien Thibault

Today, some of the world’s largest economies are considering issuing a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC), a digital form of a country’s currency that could be used to make online and mobile payments. Issued by a central bank, CBDCs could provide features that other forms of payment can’t, including superior privacy protections and anti-money laundering features. They could also enable “smart contracts,” which complete payments only after certain conditions have been met, reducing the potential for fraud.

The Bank of Canada has conducted research into CBDCs for several years, and the European Central Bank recently launched an investigative phase for a digital Euro. The United States is also exploring the possibility: in March 2022, President Joe Biden issued an executive order to seriously consider a CBDC. In all, more than a hundred countries are looking into issuing a CBDC—about triple the number just two years ago. And CBDCs are becoming ever less hypothetical: 11 smaller economies have already launched one.

Naturally, large economies have different interests than smaller ones. Improvements to existing systems could yield some of the same benefits as CBDCs, while implementing CBDCs would have an enormous impact on individuals, financial institutions, and even entire countries.

Academics, policymakers, and private sector experts recently debated these questions at the Desmarais Global Finance Lecture on the topic of “Central Bank Digital Currencies and Alternative Payment Systems” at McGill’s Desautels Faculty of Management. “We wanted to bring together a variety of perspectives,” says Katrin Tinn, a Desautels professor of Finance who specializes in digital currencies and co-organized the event with the director of the Desmarais Global Finance Research Centre and Desautels professor, David Schumacher.

“Many central banks are considering issuing a CBDC, but they have not made their decisions yet,” says Tinn. “We wanted to have opinions from Canada and the United States represented, as well as international ones to bring in a global view of what a CBDC could be.”

Addressing the most important CBDC questions

How a CBDC should work in any given context remains a multi-layered question, including what features each CBDC needs and how much privacy they should offer. As the conference pointed out, several major questions and concerns need to be addressed for CBDCs to fully function:

- Can thorough design of a CBDC ensure that it will be adopted and operation optimally?

- How inclusive are CBDCs, especially considering countries with a large proportion of unbanked people?

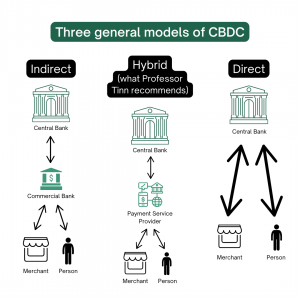

- If CBDCs create a direct link between central banks and currency users, will the middleman—retail banks—be cut out? What are the consequences and are they avoidable?

- What effects will CBDCs have on national financial policies, specifically those of Canada and the U.S.?

- What impact does FinTech innovation have on CBDCs, which need superior functionality and programmable features than existing payment methods?

CBDCs in theory and in practice

In a panel discussion, the head of the Toronto Centre of the Bank for International Settlements Innovation Hub, Miguel Díaz, joined Bank of Canada Advisor to the Governor Paul Chilcott and Stanford Adams Distinguished Professor of Management and Professor of Finance Darrell Duffie to discuss the overall challenges of designing and implementing a CBDC.

On the design level, a CBDC must be:

- Highly scalable, so that large numbers of transactions can be settled.

- Interoperable with existing systems, so that people have multiple payment options.

- Integrated into existing infrastructures that will need to accommodate CBDCs.

- Able to work across international borders in cooperation with other central banks.

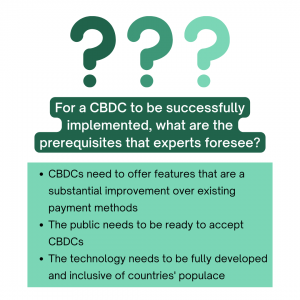

Even then, any expectation of widespread adoption is probably premature, the panelists say. While central banks may be positioned to facilitate a digital economy in some places that the private sector can’t, the public might not be prepared to accept CBDCs any time soon. Add to this the challenges that come with designing complicated new technologies, which is not a core function of central banks.

Convenience is also a critical factor. Consumers will choose to pay with their preferred method of payment, so, in order to be widely adopted, any CBDC would need to offer features that are a substantial improvement over existing payment methods.

The public might not be prepared to accept CBDCs any time soon

Ensuring digital inclusion

Central banks have a responsibility to serve their respective countries, so it’s vital that the technologies they deploy are inclusive. The fact is, currently not everyone has access to digital technologies.

In the conference’s policy keynote, Miguel Díaz addressed how CBDCs could work in countries that have a large proportion of unbanked people.

“Everything will be touched by the digital realm, and whoever is left out will be left out of society as a whole. The gap will be much more important than what we see now,” says Díaz, who spent nearly two decades with Mexico’s central bank as a managing director of financial market infrastructures.

“The stability and robustness of central banks are what gained them the trust of societies,” he says. “Central banks need to identify which elements of technology can push forward social needs. We need to anchor our work with a long-term vision. And I believe we need to focus on the functionality we provide to society, as opposed to technologies themselves. Technology is important, but it is only a tool. We need to identify the actual functions they serve. We must be careful not to end up with a marvelously complex, beautiful, and elegant piece of technology that solves no societal issue.”

Big-picture thinking is important, but the devil is in the details. For major central banks conducting research into issuing CBDCs, the fundamental question is not how to create a CBDC but whether it should be done at all.

Where retail bank transactions and lending fit in

Banks play an important role in our economy by providing financing for individuals and business models, as well as income related to existing funding. Some retail banks are concerned that a CBDC would undermine their business model.

Since at least 16th century Venice, banks have completed transactions between parties by sending money between bank accounts at the payer’s request, using tools like a written check. It is called a giro transaction, named for Venice’s Banco del Giro—although some similar systems date back to ancient times. Today’s debit card transactions use the same basic principles, with a payer initiating a request to pay another account based on money that is held in their own account.

In his keynote lecture, Darrell Duffie addressed the effects of CBDCs on bank lending. It is not yet clear what effect CBDCs would have on the financial services sector, and Duffie noted that some scenarios could even see lending increase. Yufeng Wu of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign also presented research findings on the subject.

In theory, a CBDC could make transactions more efficient by only involving one bank—the central bank. But the way that payments are made is changing, and CBDCs won’t only be in competition with traditional banking tools.

“We are in a new setting, where credit cards are the majority use case,” says Duffie. “Credit cards give roughly about two per cent back in rewards, funded by interchange fees, which are very expensive in North America. But a CBDC won’t have rewards. That is one of the issues. There is going to be an interplay of regulation and technology to get to the next payment system.”

There is going to be an interplay of regulation and technology to get to the next payment system.

Weighing incentives to upgrade banking systems

Payments will continue to evolve, but not necessarily be toward a CBDC. “[For payment systems,] we are going to be down to either two or three alternatives,” Duffie explains. “One is to upgrade the existing bank-railed payment systems. That would probably imply real-time gross settlement with instant access to money, available around the clock. Banks could, in principle, do this much more widely and inter-operably, on their own, but they do not have the incentive to create an upgraded payment system, at least not right now.”

This is because privately charging for transactions is a large part of banks’ business model. Yet that’s where central banks can potentially step in. Duffie cites the case of the Central Bank of Brazil, which introduced PIX overlay in its Instant Payment System in 2020. PIX uses real-time gross settlement to complete transactions instantly, and charges just a fraction of a cent for each one. It operates on mobile apps, and every company with more than 200,000 customers in the country must provide it. After just two years, a large majority of Brazilians have PIX installed on their phone, including 5 million people who did not previously have a bank account.

If you are not going to do CBDC, then what are you going to do?

Bringing unbanked people into the fold is one of the promises of CBDCs, but we don’t yet have a sense of their full potential—or negative impacts. More competition in the payment system could benefit consumers by keeping fees low, but some central banks have expressed concern that the issuance of a CBDC could reduce lending by banks. There is still a lot we don’t know, but Duffie sees a way forward.

“If you are not going to do CBDC, then what are you going to do? I would elevate the use of regulations and fast payment infrastructure to promote a more open, interoperable, and competitive bank-railed payment system. But I would not stop there,” he says.

“We do not yet know what digital currencies might offer,” Duffie continues. “I doubt that government will be the major source of innovation in the cryptocurrency space. Cryptocurrencies have lots of risks, but we should see what they can do. Give cryptocurrencies a chance, subject to compliance requirements. As far as CBDCs, there is no need to make a commitment yet. People want an answer: are we going to do it, are we not? Let’s do the R&D first, and then see what the capabilities are.”

David Schumacher

Featuring conference speakers: