Sustainability has officially made the leap from buzzword to policy, with organizations large and small signing net-zero initiatives and implementing more environmentally and socially sustainable management models. In the high-stakes realm of finance and investment, environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria play a larger role than ever in companies’ decisions around mergers, acquisitions, and divestitures and commitment to creating shared value. In this accelerated transition toward cross-sector economic change, whose interests are centred and whose concerns are left out of the sustainability conversation?

Article written by: Robyn Fadden

Illustration: lumerb – stock.adobe.com

In Canada, where resource industry and land investment are significant, adoption of ESG standards has proven to contribute to value creation through growth, cost reduction, regulatory and legal interventions, productivity uplift, investment, and asset optimization. However, clear gaps in the ESG landscape have recently emerged.

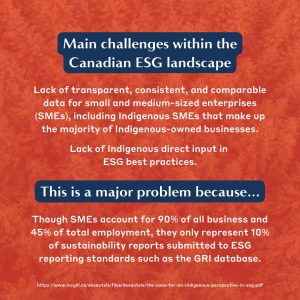

A recent research report out of the Desautels Integrated Management Student Fellowship (IMSF) program, with the support and consultation of Desautels professors, finance-sector experts, and Indigenous business owners, found an absence of Indigenous notions and viewpoints in ESG reporting standards such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). Additionally, the report found that a lack of Indigenous inclusions comes at a high opportunity cost to non-Indigenous small-to-medium enterprises.

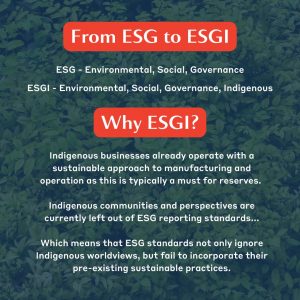

The IMSF team focused on how to include Indigenous communities in a sustainability context by proposing best practices related to ESG. An Indigenous perspective on ESG—nascently termed ESGI—could point the way forward for more inclusive, equitable, and truly long-term sustainability policies in investment.

Hits and misses in current ESG standards

Commitment to sustainable investment through the adoption of ESG standards is quickly becoming a requirement for successful investment managers and corporations. In recent research on the investment strategy of large Canadian pension funds, Desautels Finance professor Sebastien Betermier found that the growing integration of ESG into corporate business models can encourage demand for pension funds to invest in green urban development. The future is being built on sustainability—the question is, what constitutes its foundation?

ESG metrics lack clear standards or requirements pertaining to Indigenous communities and how to work with them efficiently.

As a set of guiding principles that help investors screen companies’ performance through a socially conscious lens, ESG criteria cover a wide range of activities, including environmental stewardship, relationships between companies and the communities they operate in, the leadership of an organization, and shareholder rights. Financial services companies worldwide use ESG metrics to identify, measure, and mitigate non-technical risk, publishing annual reports that extensively review their ESG approaches and bottom-line results. These are crucial to receiving loans, grants, and other funding, in addition to having the social permission to operate. Yet even organizations within the sustainable finance management field define and address ESG metrics differently.

In researching the breadth of ESG metrics within a broader context of including Indigenous rights and worldviews in the current socio-economic sphere, the IMSF fellows found that ESG metrics lack clear standards or requirements pertaining to Indigenous communities and how to work with them efficiently. That research, alongside interviews with Indigenous business leaders, also revealed that direct Indigenous input is absent from ESG best practices.

Research and conversation reveal ESG gaps

An experiential leadership development program coordinated by the Marcel Desautels Institute for Integrated Management, the IMSF is an opportunity for students to explore an issue and its feasible solutions, including how they can implement findings that will have a real-world impact on that problem.

“In the case of the ESG project, it became very apparent that there is a glaring gap when it comes to ESG metrics and reporting, including how underserviced and how unsatisfying it is for certain demographics of society who are not represented in those metrics, and it actually works against them,” says Dr. Sabine Dhir, Acting Director of the Marcel Desautels Institute for Integrated Management and an IMSF professor.

The research team members looked at areas that straddled their interests in finance and environmental issues in Indigenous communities in Canada: investigating ESG metrics fit perfectly, and lead to the discovery that Indigenous communities are excluded from decision-making around ESG standards.

It is already a challenge for ESG metrics to be fully included in the long-term potential of traditional finance firms.

“We found that, for instance, some investment management firms have ESG teams, and usually those teams would make recommendations on certain investments improvements, but they always fail against the traditional investors that have the last word,” says Tom Berger, one of the four team members. “So, it is already a challenge for ESG metrics to be fully included in the long-term potential of traditional finance firms.”

“With ESG and other finance principles and accounting, it’s very regulated,” team member Khaled Khadam adds. “I don’t think a group of students can necessarily implement change, but what we can wish for is that someone with more influence and power, whether in government, policy, or anyone making ESG-related decisions, could affect changes in the way financial reporting is done by understanding this issue and implementing it.”

Indigenous points of view complete the big picture

Through both quantitative and qualitative research approaches, the fellows found that “persistent challenges hamper Indigenous economic prosperity, and sustainability and social impact are integral to Indigenous businesses. Indigenous perspectives/principles thus constitute wise practices to tackle the complexity and uncertainty of the times we live in and ensure the welfare of others.”

“Access to the information itself was a challenge,” says Berger. While ESG metrics are diverse, most are available readily online. However, Indigenous worldviews on ESG is a complex, under-researched topic. The fellows found that most finance-related research emphasized economic empowerment of Indigenous communities, rather than what they contribute in terms of finance and investment standards.

Among the projects’ sources, a recent report from the First Nations Major Project Coalition identified the absence of Indigenous notions and viewpoints in the main ESG reporting standards, such as Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB). The IMSF fellows note in their report that such omissions raise an important question: “How can ESG-approved investments be deemed to be responsible or to even meet the spirit of ESG criteria if their impact upon Indigenous Peoples rights have not been vetted by Indigenous communities?”

In early 2022, the IMSF research team conducted interviews with Indigenous business owners to include real-world perspectives and gain insights that only members of Indigenous communities can attest to.

“Our selection criteria for businesses were based on three things,” explains team member Anna Abramova. “First, we wanted to have a balance of businesses that operate on and off the reserve to see whether the location of the business matters in the challenges they’re facing and whether they’re dealing with these challenges differently. The second was related to the area in which these businesses operate, since we wanted to have a diverse sample that’s not reflective of problems in a specific industry—we had businesses that dealt with food production, medical supplies, construction, a variety of different industries. The third factor wasn’t something that we considered initially but is also an important one: we interviewed both female and male business founders to highlight the gender diversity of these entrepreneurs.”

Their conversations identified key insights on: working with non-Indigenous partners and barriers to financing; the question of an Indigenous business identity; and sustainability and social impact.

Despite recent attempts for reconciliation, Indigenous business owners highlighted Indigenous-specific barriers to financing, such as challenges in securing funding and loans from the public sector. In addition, they experienced difficulty working with the government, especially at the provincial level.

Indigenous communities have historically mostly “supplied themselves sustainability.”

“At the end of the day, it may be harder than for non-Indigenous businesses, but banks want to lend, and it ends up working out usually, they don’t care about color of your skin; the real issue is with public funding—most barriers come from governmental institutions,” Indigenous business owner Leo Hurtubise told the researchers.

The report notes that Hurtubise said that his businesses operate with a sustainable approach to manufacturing and operation, just like Indigenous communities have historically mostly “supplied themselves sustainability.” According to him, being mindful of the environment in business yields financial advantages in addition to preserving ecosystems. In reserves though, as in most Indigenous communities, he mentions that this is a must, not a plus.

“The reason that Indigenous people and communities have been excluded isn’t as simple as it may seem,” comments team member Nabil Anouti. “There are complex levels to why access to capital isn’t straightforward for Indigenous communities. Part of that is about uncovering the more systemic challenges. It was very humbling, interesting, and rewarding to get that perspective and understand how it can be leveraged to improve access to financing for Indigenous communities and contribute to wider discussions around equitable access to capital and opportunity in Canada.”

Future directions for ESG

The fellows see their research as a springboard for further research on the topic, as well as an example of the impact of experiential learning through research outside the classroom and campus. “We noticed very quickly that you can’t do this in a bubble. You need to do interviews, you need to be on the ground and do the research,” says Anouti.

Today, applying an ESG vision that integrates an Indigenous perspective (ESGI) is more common among government entities—a reflection of fewer incentives for financial and investment firms to integrate ESGI. Encouragement to link investments with sustainability could unlock the wider potential of ESG metrics, including Indigenous metrics that reflect Indigenous worldviews.

“People working on similar issues in the future, specifically regulators and legislators who will be incorporating Indigenous perspectives into ESG metrics, will face the paradox between a goal to standardize these metrics and to incorporate Indigenous perspectives that vary from continent to continent, from region to region,” adds Abramova. “They’ll have to find a careful balance between the two; that will be a big challenge.”

Read the full report, ESG: The Case for an Indigenous Perspective, including further insights on ESG metrics and value creation, and first-hand accounts from Indigenous business owners. Find out more about the Integrated Management Student Fellowship (IMSF) and its links to research-based thought leadership at Desautels.

Desautels IMSF fellows: Anna Abramova, Khaled Khadam, Nabil Anouti, and Tom Berger

With research support from Desautels professors Benjamin Croitoru, Dongyoung Lee, Karl Moore, and Sabine Dhir; further input from Erikk Opinio, Responsible Investment Analyst at AIMCo, and Maira Maisuradze, CEO of Education for Sustainability; and interviews with Indigenous business founders Leo Hurtubise (Nipissing First Nation, Ojibwe – Founder, La Flesche & ATD Manufacturing), Jacques Watso (Abenaki First Nation – Founder, Sagamité Watso), and Kelly McBride (Timiskaming First Nation – Founder, Weesanin).